Anti-aging is a weird term. It’s like anti-air, or anti-water. How can you be against it? Why do we think we can fight aging?

The anti-aging logic is flawed, and preventing aging is futile. That won’t stop researchers and product developers from aggressively pursuing “anti-aging” genes or pills. Certainly the appetite for such cures will remain strong and ready to be exploited.

Instead, I think it is much more productive to focus on improving the quality of life. We need to focus on adding life to years, not just years to life. This mindset shift leads us to proven solutions to living a better life.

Haven’t we done a good job by increasing life expectancy?

Medical advancements have had a tremendous impact on increasing life expectancy. Treatment of infections, traumas, and organ transplants are just some examples of medical advances that have significantly improved life expectancy. From 1900 to 2007, life expectancy rose from 49.2 years to 77.9. This is a huge accomplishment to be proud of. But successfully increasing life expectancy has overshadowed 2 major problems: A lack of effectiveness in treating chronic conditions and the quality of life has not necessarily improved.

Increasing life expectancy was mostly related to decreased peri-natal deaths and infectious disease. So these increases were mostly due to treating conditions that affected younger people. If we move from analyzing our impact on improving life expectancy from treating acute infections to chronic diseases, we would have to look at different life expectancy figures. The way to do this is to see how much the life expectancy increased for those living past 65 years old. In the last century, a person older than 65 increased life expectancy by only 6 years. In the last 20 years, the life expectancy for those older than 65 has increased only 1 year. Clearly our impact on extending life in the face of chronic conditions is less impressive

More years, not better years.

An alarming trend is clear when analyzing research about the aging process. Over the last several decades, while the number of years someone can expect to live has increased, the number of “quality years” has not. In fact, the number of years someone can expect to live without significant loss of function and disease has actually decreased! This is exemplified by a recent study showing that the Length of life with disease and mobility functional loss has increased between 1998 and 2008. (Crimmons, et al. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci (2011) 66B (1): 75-86.). We are living longer, but not better.

A key term we must understand in addressing this issue is Morbidity, which is defined in relation to aging as the existence of disease or medical condition and the burden or functional disability it causes. So morbidity is living with high blood pressure and high blood sugar requiring medical management and not being able to ascend stairs, get on and off the toilet independently or travel.

This clearly tells us that rather than seeking methods to prolong life, which we have succeeded at, we should instead focus on improving the quality of these years. This does not mean that we give up on efforts to prolong life, but rather increase the emphasis on the need to address morbidity, especially considering the simplicity and effectiveness of strategies available to do so. The questions that this raises are: how do we reduce morbidity and is there evidence that this is possible?

The compression of morbidity

It is inevitable that we will succumb to disease and disability as we near death. There will usually be some morbidity leaning up to mortality. If it was within your control, would you rather choose to be ill and unable to function for several years as you slowly die, or have normal function before briefly falling ill for a few months before dying? I’m sure we would all strive towards the later scenario.

This concept is referred to as the compression of morbidity: shortening the inevitable decline of function that proceeds death to months as opposed to years. Interestingly, there is some great research to suggest that this is certainly possible.

Is the compression of morbidity possible?

Recent research has found that we can significantly reduce morbidity

Hubert HB, Bloch DA, Oehlert JW, Fries JF. Lifestyle habits and compression of morbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 Jun;57(6):M347-51. This study was performed at Stanford involving 418 adults over 12 years. Those who had less risk factors for disease lived more years without morbidity.

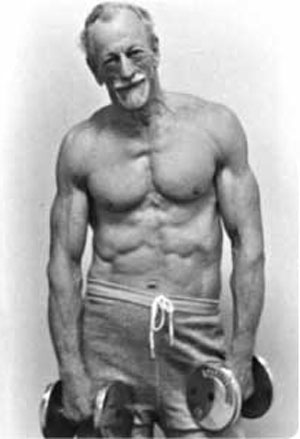

Several other studies support this concept. I recently wrote here about how strength can be improved in older men to levels similar to men half their age with proper training in 12 weeks. Other studies have seen that people can retain 100% of their muscle mass and strength from age 40 through their 80s with exercise! (Wrobelski, A. et al. The Phys and Sports Med, Sept 2011)

Countless studies show how exercise plays a dramatic role in reducing morbidity. One particular study looked examined lifestyle habits of older adults who lived passed 85 and had no disability prior to death. The most significant variable associated with living without disability was level of physical activity after 65. Those who were physically active had a two-fold increased likelihood of dying without a disability. (Levielle, et al. Am. J. Epidemiol. (1999) 149 (7): 654-664)

What about those we are already very frail and deconditioned? Are they “too far gone” to reap the benefits reported on exercise to reduce disability? I sadly come across the perception held by many patients and worse by clinicians that the most frail elderly are not capable of benefiting from exercise interventions to reduce disability. Good thing there’s research to lend some insight. Researchers from Tufts showed that not only did frail older adults benefit from exercise, they actually benefited the most! They had higher improvements in strength and function. Guess what type of exercise yielded these results? That’s right – high intensity resistance training. (Fiatarone, MA, et al. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1769-1775)

Clearly, reducing morbidity is possible and should be a major emphasis for health care policy and how we elect to take care of ourselves. It is something that we should focus on whether we are young and in shape or older and deconditioned.

How do we do this?

Enhancing strength is the simplest route to reducing morbidity. Strength has been linked to mortality in older adults. It is the most important variable in reducing falls, preventing sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass), preventing osteoporosis – all conditions that plague us as we age and contribute to mortality. Resistance training has shown to be a vital treatment for preventing and managing osteoarthritis, improves glucose metabolism (the basis of type 2 diabetes), and reduces the risk or heart disease. As the most effective exercise for fat loss, it helps in managing obesity. It is the primary or one of the most effective treatments for addressing the most common causes of death (CAD, stroke, obesity) or morbidity (falls, sarcopenia, osteoporosis), especially in older adults. And considering it’s role in pain management and improving mood, it should be clear that resistance training is especially important if adding life to years is something you are interested in. If there is one thing to do to improve the quality of life as we age, strength training would be it.

Unfortunately, many people are unaware as to what strength training is. Some assume that doing dumbbell curls, balancing on a swiss ball, or doing leg extensions at the gym constitutes and effective strength training program. Many are confused about how much weight, how many sets and repetitions, how many exercises, etc are best. Others have no idea how to do their program safely and effectively. It usually boils down to two issues:

- how to design a proper program (ie the dosage: what to do, how much, when, etc) and

- instruction (how to do it, providing cueing and feedback, etc).

Everyone needs help with these two issues, from professional athletes to the morbidly deconditioned and everyone in between. Some need less than others, but they will all need assessment, program design, instruction, and accountability. And that is exactly what we do at Spectrum. I am passionate about making sure people realize this so they receive the proven benefits a proper program can provide them.

If you want to see some videos of some of our older clients showing some examples what proper strength training looks like, check this out.

Long Live The Anti-Morbidity Movement!

It seems to make more sense to focus on a proven strategy that is right under our nose to dramatically improve our quality of life, rather that hold out for hope that someone will be able to defy the cellular mechanism of aging. Although researchers seems to have found that aging occurs because cells begin to die faster than they can regenerate ( cell senescence), no one has determined how or if that can be changed. I’m sure the riddle will involve a relation between lifestyle variables amongst other things having an impact on the cellular mechanisms of aging.

In the meantime, it seems dangerous to ignore the tenant of the compression of morbidity. Ask anyone who is near the end of the life span – they will tell you the same.