Pain is a powerful force. It is feared and respected. It is the most common reason for which we seek medical advice. Learning how to manage it, prevent it, and eliminate it is incredibly empowering. That’s why I’m excited to share some thoughts about pain and exercise.

It is not uncommon to suffer pain unrelated to exercise, and wonder if exercise or certain activities will help or irritate the cause of pain. Accordingly, I want to pass along some perspectives about managing, treating, and preventing pain as it relates to exercise.

2 Pain Disclaimers

1. Don’t ignore it or trivialize it.

The bravado about ignoring pain is mostly B.S. Pain is not to be ignored, it to be understood. Pain serves a great purpose in the human experience. If you aren’t convinced, then imagine what life would be like if we didn’t have the sensation of pain. Thanks to a rare congenital disease that only affects about 35 people in this country a year, we can know exactly what it would be like to be without pain. Most afflicted with this disease will not live past 3 years old, and the longest life expectancy is 25 years. The crippling effects of infections and traumas that can’t be detected take an extreme toll. Clearly, pain is essential.

2. Pain is a very complex and multidimensional phenomenon. Obviously, no article or instruction can possibly do justice to explaining the complexities of pain. That probably explains why I have started and stopped this post about 20 times. However, it is best to have some general guidelines. What follows can serve just as that, which I hope will be very helpful to you!

Now that we except that pain is complex, purposeful and not to be ignored, lets discuss some practical aspects of pain as it relates to exercise.

The pain traffic light: Go or No Go?

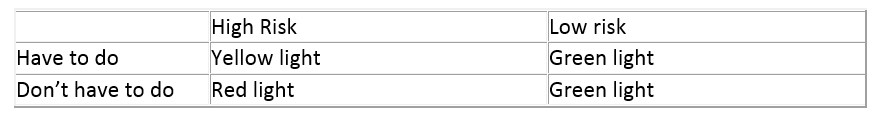

This is a very basic tool I use to help decide if a certain activity should be performed when someone has an injury or a potential for re-injury. I call it the pain traffic light, and it is really a simple grid.

So here’s how it works. Let’s say your back pain has been acting up. You have a history of disc injury. It is painful any time you sit for prolonged periods of time or bend to put your socks on. You are wondering about what activities you should do this week. Activities in question are going to work and exercising.

Let’s take going to work, which in our hypothetical case involves prolonged sitting: In most cases, you have to do this, that is – go to work. But it is high risk, because you are sitting at a computer most of the day, which is known to contribute to back pain.

So what do you do? I’ll answer this in the context of the optimization versus avoidance strategy

Avoidance versus Optimization Strategy?

If we apply the above grid, and we assume that for whatever reason staying home isn’t an option (job security, tight deadline), we can see that the issue of going to work yields a yellow light. This means we need to proceed with caution, because pain or injury is possible if you choose this activity.

In dealing with pain and injury, you have essentially 2 strategies: avoid the activity that is causing the problem, or optimize how you do the activity so as not to experience the damaging effects of participating in the activity, as well as avoiding the consequences of not partaking in the activity.

Perhaps a third benefit of the optimization strategy is the ability to learn how to manage and prevent future occurrences of damage and injury. As you can imagine, most activities when applying the go or no go pain traffic light fall into the yellow light, and thus the optimization strategy of treatment.

Getting back to this specific example, let’s apply the yellow light optimization approach to our sitting at work with back pain scenario.

First, the patient needs to inherently understand the risks of prolonged sitting on disc health – so education here is key. Second, we need to understand that position while sitting can increase or decrease the stresses experienced by the spine while sitting. For example, most will typically sit with a flexed posture, thus increasing the stress the discs experience while sitting. We can minimize the stress the spine experiences by sitting with a neutral lordosis, thereby optimizing the spine’s position to disperse load across the structures of the spine. However, this doesn’t address the negatives of prolonged sitting. Even if we maintain neutral spine while sitting, we still experience stresses that can aggravate existing spine problems. Also, the ability to sustain neutral spine can be limited because of endurance issues and attention issues (we tend to lose focus on posture over time). So, we enlist a few simple strategies centered around interrupting prolonged postures:

1. Deload: briefly relieve the accumulation of pressure on the spine for several sets of 10 second holds by pushing your arms down on your seat, lessening the pressure on your spine. For a more complete description on how to do this, click here. Do this every few minutes or so. There are many alarms you can use (check google) as discrete reminders if needed.

2. Get up frequently. Simply, get out of your chair every 5-30 minutes and either stand or walk around. Just a few seconds can help. Standing to take phone calls is a good reminder to get up.

In pain: to exercise or not?

Let’s address another common scenario using this case and the pain traffic light grid. In this same example, our person with acute back pain, is also wondering whether he should exercise. At the outset, this seems pretty obvious. Exercise is risky, and you don’t have to exercise, so this is clearly a red light right? No – not right at all. Here’s why.

Quite simply, exercise is not risky, that is if you are doing it correctly. That means you have a program design that is scalable, and you have proper technique. Furthermore, we could classify exercise for many people as “have to do”, especially if you are considering the profound benefits. But even if we stay in the strict limits of the grid, we can certainly classify exercise with acute back pain in this case as a yellow light. Choosing to exercise as a means to manage and solve pain can be one of the most important learning experiences for optimizing performance and function.

It might be hard to imagine that exercising with acute back pain is a good idea, so let me walk you through a specific example. And before I go on, this isn’t going to be “pain is all in your head” or “no pain no gain” garbage philosophy. Just real experience played out hundreds of times.

In this case, upon exam it is clear that this person has pain with flexing the spine, loading the spine, and keeping the spine in prolonged static positions. This is not a problem, because proper exercise does not require any of these stressors to be effective. Here’s how I have successfully approached this common case:

- Extensive education on the above. I would also reference issues I’ve described in depth about Low back pain here and here as well. When you are in pain, the only thing that makes senses initially is protect and avoid. Most don’t see exercise as part of this idea, but it is- it just needs some explanation first.

- Now that it is accepted that exercise will not impose the stressors on the spine that replicates spine damage and pain, we proceed to target critical movements that will make for an effective exercise program, pain management strategy, and injury prevention strategy. Here are two examples of seemingly “Red Light” exercises that are perfect options for treating, managing, and preventing back pain and how they would be applied in this case:

Squat: seeing as we must get on and off toilets and chairs, it would be a good idea to re-examine the concept of a hip hinge in neutral spine. That simply means teaching someone to bend at the hips, not the waist, to spare the spine of irritating forces. Depending on the person, we may need to completely eliminate any external load and in some cases, we may even need to deload below body weight. This is still productive from an exercise standpoint because it hones proper technique. Pain is a great teacher, and if you do the hip hinge correctly while in pain, you will know it right away. Teaching someone how to squat while in pain is the quickest way to learn proper squatting. It is also the quickest way to reduce symptoms, because you make an everyday activity that was once painful, pain free.

Lunge: the same concepts as above apply, except you are now increasing load on the legs without increasing load on the spine. With a lunge, you are putting nearly your entire weight on one leg, so it is more of a stress on the leg muscles, but you don’t have to add any more weight to your spine, so it is a better fitness stimulus without the penalty. Also, it gives you another pain free movement strategy to move down to and up off the ground, and further ingrains the motor pattern of the hip hinge.

There’s much more to this, but the point is to get an appreciation for the go or no go application of the pain traffic light, especially by illustrating a common example.

Again, I hope I can impress upon you that there are no simple explanations of pain and accordingly simple rules to follow in all cases. But hopefully these pain traffic light grids can help you in deciding whether you should do an activity and if so how to proceed. At the very least, it can give you a frame work to apply some good decision making as you learn more about your body, and a better appreciation for the science and art of interpreting your body’s signs, which brings me to one final point…

“Listening” to your body?

I want to finish this by addressing a common suggestion for deciding how to manage pain as it relates to activity. I always hear the people saying “Just listen to your body”, and it conjures up the same feeling when I hear “Just eat right and exercise”, or “save money and spend less”. My response is always, “gee, thanks, but the issue is how the heck do you do that!”

Listening to your body is really a skill. There are 2 types of people who are particularly gifted with this skill:

1.) Athletes or highly active and motivated people that have experienced multiple types of pain from injury and pushing the body to the limits and

2.) Clinicians who have studied the body and are charge with the responsibility of interpreting, treating, and managing multiple types of conditions and people producing and experiencing pain.

And sometimes, there is a third type of person – someone who is both 1 and 2! I have the somewhat dubious distinction, yet priceless perspective of being that person!

So the best way to listen to your body, if you don’t want to become a clinician, or are not a highly trained athlete, is to spend some time with someone who can teach that skill. Like an auto mechanic that makes sense of the mysterious squeaks and squeals your car makes, the right professionals can turn your pain complaints into a treatable plan to optimize your function. Click here to learn how.